IPFS is a protocol suite for a content-addressed networking. If you’d like to run a node and participate in the peer-to-peer network, by all means give it a try!

The most important thing to get: with IPFS you can fetch something by a Content ID (CID), which represents what it is, not where it’s coming from.

The other way of fetching things from the IPFS ecosystem is through IPNS, which allows someone to cryptographically sign a reference to a CID, then you can request whatever content that person/organization is currently pointing to as their site.

Essentially, http:// specifies “where” to find it, ipfs:// specifies “what” to find, and ipns:// specifies “whose” content to find.

What about people who don’t know about IPFS, and just run across a link? What if they’d like to be able to use that link in their browser? This is where a “client” fits in — software that can talk to nodes to fetch the content they want, but without running one yourself.

What is this all about?

Most IPFS clients talk to a particular HTTP gateway. Multi-Gateway Clients proposed in IPIP-359 fulfill your requests using multiple Trustless Gateways. This gives you more resilience, as you’re not dependent on a single HTTP endpoint that can be censored or blocked by your ISP. It also can result in better performance, as you can multiplex requests that would typically run through a single server.

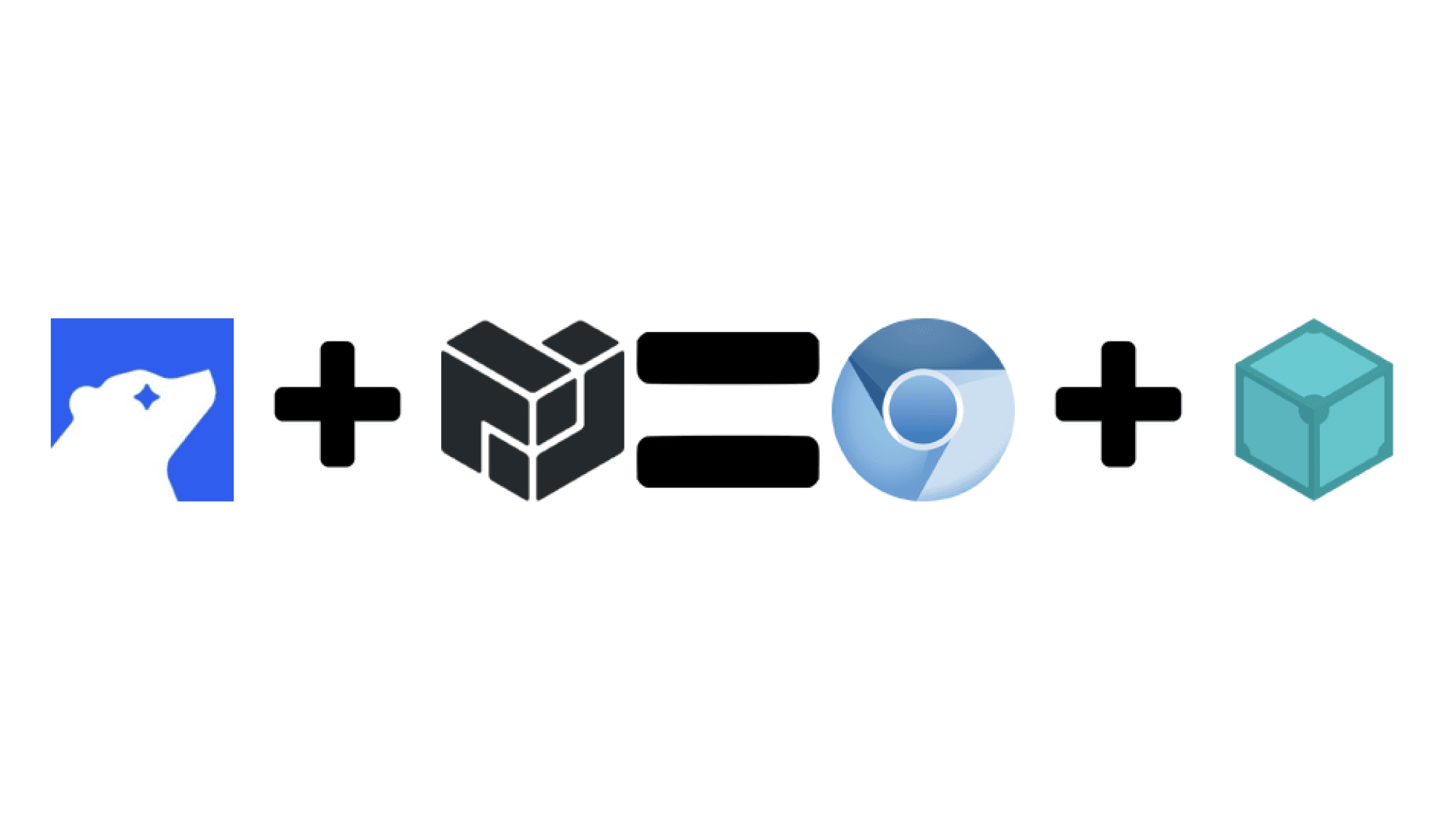

Here we’re talking about a project to implement IPFS in Chromium. The result is an experimental racing multi-gateway client built directly into the browser, which means the same request might get sent to multiple Trustless Gateways, and the first one to get the result verified wins. And it’s built into a custom-patched build of Chromium.

Why build this?

This is by no means the first time IPFS has been usable in a browser, or even Chromium-based browsers in particular. Javier Fernández at Igalia has written some good explanations of other approaches that have been taken over at his blog in his post Discovering Chrome’s pre-defined Custom Handlers, and there’s an overview on the IPFS blog as well.

Most of these approaches share in common the idea of translating IPFS and IPNS requests, 1:1, into HTTP requests. For example, if you have an HTTP gateway running locally on your machine, something like:

ipfs://bafybeihpy2n6vwt2jjq5gusv23ajtilzbao3ekfb2hiev2xvuxscdxqcp4

might become:

http://localhost:8080/ipfs/bafybeihpy2n6vwt2jjq5gusv23ajtilzbao3ekfb2hiev2xvuxscdxqcp4/

Or maybe it could become:

https://ipfs.io/ipfs/bafybeihpy2n6vwt2jjq5gusv23ajtilzbao3ekfb2hiev2xvuxscdxqcp4/

Or preferably (when Origin isolation matters):

https://bafybeihpy2n6vwt2jjq5gusv23ajtilzbao3ekfb2hiev2xvuxscdxqcp4.ipfs.dweb.link/

In each case, you’re delegating all the “IPFS stuff,” including CID (hash) verification, to a particular node. This is effective for completing requests, but has some trade-offs, including the privacy and integrity risks when using a remote gateway provided by a third-party.

Performance

If the gateway you’re using happens to have the data you’re seeking already on-hand, your performance will be great, since it can simply return to you what it already has. Performance might even be better than the multi-gateway client, since no extraneous requests would be made. However, if you were unlucky, that gateway will have to spend more time querying the IPFS network to try to find the data you request before it gives up. The ideal gateway to use may very well depend on what you happen to be doing at the moment — and may differ from one of your tabs to another. A multi-gateway client will have the worst case performance more rarely.

And while we’ve been talking about “files” for the most part, IPFS breaks larger files down into “blocks”. So you can apply these same techniques at the block level, and it’s also conceivable that for a sufficiently large file which exists on multiple gateways you’re talking to, a verifying multi-gateway client might be able to be faster than a single-gateway client, since you might be pulling down parts of the file from different sources concurrently. RAPIDE is a more advanced in-development client which also makes use of this principle (along with other things). And it’s showing promising results — watch a recent talk from IPFS Thing by Jorropo on it!

Installation (vs. local gateway)

If you’re reading this, installing a local node might seem like no big deal to you. However, we want IPFS to be accessible to people who haven’t heard of it, and make it easy for them to click a link without having to think about which protocol-handling software they have installed ahead of time.

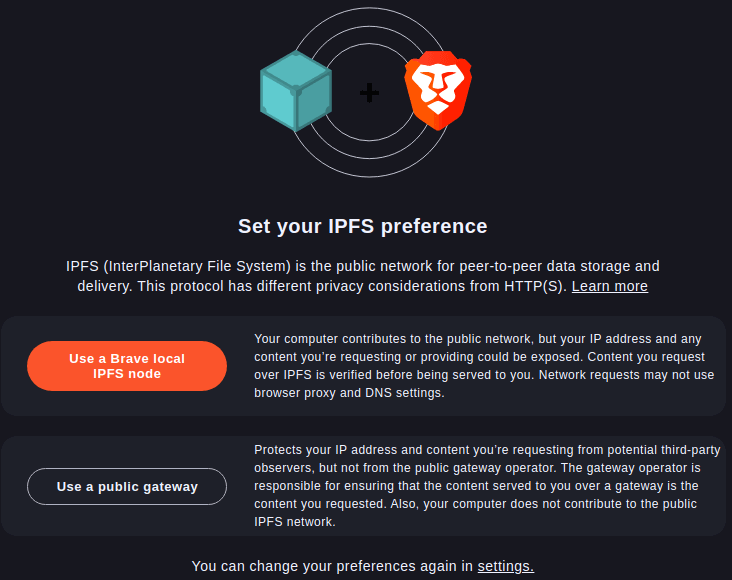

One approach is to have the browser install and start its own IPFS node. This is a pretty reasonable approach, but it can raise questions about when to dedicate resources to installation or the node’s daemon. The most notable example of this approach is Brave.

However, regardless of whether the browser manages a Kubo node as Brave does or implements IPFS natively, the architecture of the application has changed in a significant way — from being strictly a client, to being a server.

Including HTTP-client-only IPFS capabilities in a Chromium-based browser doesn’t change the installation experience in a noticeable way, nor require any major rethink of the browser security model.

Security (vs. single public gateway)

Content-addressed networking involves a validation step to make sure that the data you received matches the hash requested (it’s a part of the CID). When you’re requesting a file from an HTTP gateway, by default, the verification of the content is delegated to the node running the gateway. Further, if you receive the file in its final deserialized form as a response to a single request, naively using just an HTTP client, it’s no longer possible to verify locally.

This is probably fine if the gateway you’re talking to is one you’re running locally. Presumably you trust that software as much as you trust your own browser.

The public IPFS gateways today appear to be consistently and reliably returning the correct results. Nonetheless the possibility exists, and it would be preferable if we didn’t have to trust. That’s why this experimental Chromium implementation uses the Trustless Gateway API and verifies the retrieved content locally.

Where is the code?

In the repo you’ll see separation between component and library, where the former contains Chromium-specific code, and the latter contains code that helps with IPFS implementation details that can build without Chromium.

This distinction disappears when you switch over to the Chromium build. Both sets of source are dumped into a component (basically a submodule) called ipfs, that implements the handling of ipfs:// and ipns:// URLs.

Those who embed Chromium into another application generally provide an implementation of a couple of interfaces, namely ContentClient and ContentBrowserClient. They would need to add a little code to their implementations to use the ipfs component. Our repo contains a patch file which alters Chrome’s implementations of these two as a demonstration to show how usage might work. That patch file might be useful as-is to someone who uses a patching approach to make a Chromium-derived browser.

How (in more detail)?

Hooking into Chromium

- The ipfs:// and ipns:// schemes are registered in ContentClient::AddAdditionalSchemes, so the origin will be handled properly.

- An interceptor is created in ContentBrowserClient::WillCreateURLLoaderRequestInterceptors, which just checks the scheme, so ipfs:// and ipns:// navigation requests will be handled by components/ipfs.

- URL loader factories created for ipfs and ipns schemes in ContentBrowserClient::RegisterNonNetworkSubresourceURLLoaderFactories, so in-page resources with ipfs:// / ipns:// URLs (or relative URLs on a page loaded as ipfs://), will also be handled by components/ipfs.

Issuing HTTP(S) requests to Trustless Gateways

The detailed steps of the algorithm are laid out in the design doc, but here’s the basic idea:

- An IPFS link will have a CID in the URL. This is the root of its DAG, which contains directly or indirectly all the info needed to get all the files related to the site, and will be the first block needed to access the file/resource.

- For any given block that is known to be needed, but not present in-memory, send requests to several gateways which haven’t responded with an error for this CID yet and don’t currently have pending requests to them. These requests have ?format=raw so that we’ll get just the one block (with Content-Type application/vnd.ipld.raw), not the whole file.

- When a response comes from a gateway, hash it according to the algo specified in the CID’s multihash. Right now, that has to be sha-256, and luckily it generally is. If the hashes don’t match, the gateway’s response gets treated much like an error — the gateway gets reduced in priority, and a new request goes out to a gateway that hasn’t yet received this request.

- If the hashes are equal, store the block, process the block as described in Codecs (below). If the new node includes links to more blocks we also need, send requests for those blocks.

- When the browser has all the blocks needed, piece together the full file/resource and create an HTTP response and return it, as if it had been a single HTTP request all along.

Codecs

If a CID is V0, we assume the codec is dag-pb (see below). Other CIDs specify the codec, and right now we support these 2:

raw (0x55) — A block of this type is a blob — a bunch of bytes. We’ll populate the body of the response with it.

dag-pb (0x70) — That’s undefined-encoded undefined. A block of this type is a node in a DAG, and contains some bytes to let you know what kind of node it is. There is one very special and important type of node ipfs-chromium deals with a lot:

UnixFS Node

The payload of these nodes have another ProtoBuf layer, and the DAG functions in a conceptually similar way to a read-only file system.

Not all kinds of UnixFS nodes are fully handled yet, but we cover these:

File (simple case)

These nodes each have a data byte array that is the contents of a file. We’ll use those bytes as the body of a response.

File (multi-node)

In UnixFS a node can represent a file as the concatenation of other file nodes, to which it has links. The decision to use this kind of node generally has to do with the size of the file. A single node can’t be much more than a megabyte, so files larger than that get cut into chunks and handled as a tree of nodes. There are a couple of reasons for that:

- Data deduplication (it’s possible the same sequences of bytes, and thus same CID, appears in multiple files or even within the same file)

- In the case that a gateway were malicious, we wouldn’t want to wait until a file of potentially unbounded size finishes downloading before we verify that it’s correct. “ipfs-chromium” enforces a limit of 2MB per block.

- It enables the possibility that one could concurrently fetch different parts of the file from different gateways.

If we have all the nodes linked-to already, we can concatenate their data together and make a response body out of it. If we don’t, we’ll convert the missing links to CIDs and request them from gateways.

Directory (normal)

In this case the data field isn’t really important to us. The links, however, represent items in the directory.

- If your URL has a path, find the link matching the first element in the path, and repeat the whole process with that link’s CID and the remainder of the path.

- If you don’t have a path, we’ll assume you want index.html

- If there’s no index.html we’ll generate an directory listing HTML file for you.

HAMT (sharded) Directory

This is for directories with just too many entries in them to fit in a single block. The links from this directory node might be entries in the directory or they might be other HAMT nodes referring to the same directory (basically, the directory itself is getting split up over a tree of nodes).

- If you’re coming in from another HAMT node, you might have some unused bits of the hash to select the next child.

- If you have a path, hash the name of the item you’re looking for, pop the correct number of bits off the hash, and use it to select which element you’re going to next.

- If you don’t have a path, we’ll assume you want index.html.

- We don’t generate listings of sharded directories today, and this isn’t a high-priority as it’s an unreasonable use case.

Dealing with ipns:// links

The first element after ipns:// is the “ipns-name“.

- If the name is formatted as a CIDv1, and has its codec set to libp2p-key (0x72), ipfs-chromium will retrieve a signed IPNS record of what it points at from a gateway, and then load that content.

- The cryptographic signature in the record is verified using the public key, which corresponds to the “ipns-name”

- Note: only two multibase encodings are fully supported for now: base36 and base32. If your IPNS or DNSLink record points to something base58 that should work, but otherwise avoid it (don’t use it in the address bar!).

- If the name is not formatted as a CIDv1, a DNS request is created for the appropriate TXT record to resolve it as a DNSLink.

IPNS names may point to other IPNS names, in which case this process recurses. More commonly they point at an IPFS DAG, in which case ipfs-chromium will then load that content as described above.

Bottom Line

So, in the end, the user gets to treat ipfs:// links to snapshotted data like any other link, gets the result in a reasonable timeframe, and can rely on the data they get back being the correct data.

ipns:// URLs of the DNSLink variety rely only on DNS being accurate. Regular ipns:// URLs, however, are verified by the cryptographically signed record.

Trying it out

If you want to try this yourself today, you can build it from source, or you may install a pre-built binary from GitHub releases or an IPFS gateway.

If you’d just like to see it in action, here are the links I use in the video below:

- ipfs://bafybeigchjo5f3jyzfjwmbavhr27jwdhu6wwhsodxg4qq4x72aasxewp64/blog.html — a snapshot of this blog post

- ipns://k51qzi5uqu5dkq4jxcqvujfm2woh4p9y6inrojofxflzdnfht168zf8ynfzuu1/blog.html — a mutable pointer to the current version of this blog

- ipns://docs.ipfs.tech — The IPFS documentation.

- ipns://en.wikipedia-on-ipfs.org/wiki/ — Wikipedia, as a big HAMT + DNSLink

- ipns://ipfs.io — an unusual case: a DNSLink to another DNSLink

- https://littlebearlabs.io — an HTTPs URL for comparison.

When could this be widespread?

This is very experimental, and will not be in mainstream browsers tomorrow. Feel free to vote for the issue where we discuss its future.

Who is doing this?

Little Bear Labs and Protocol Labs

This article was originally posted at ipfs.tech.